This report provides a basic overview of the status of islet transplantation, one of the four Practical Cure pathways. The JDCA will publish an overview of each of the other three Practical Cure pathways over the coming months. We start with islet transplantation because there is extensive history of human testing and some of the results are surprisingly positive.

Basic definition

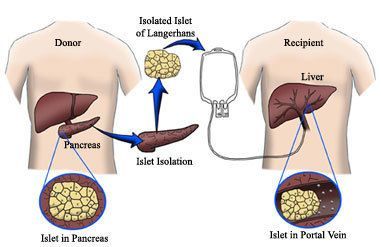

In its simplest version, islet transplantation is a procedure that combines both islet cell supply and ongoing cell protection. The approach usually has three main parts:

- Securing a source of fully functioning, insulin-producing cells

- Inserting those cells into the body through a simple surgical procedure

- Keeping the transplanted cells alive with some form of protection, such as immune suppression or encapsulation.

Two key unresolved challenges

- First, the only proven source of islets is recently deceased humans. As a result, supply is very limited. Although researchers are testing other sources of supply, including human stem cells and islet cells from other animals, the work is still far from successful human trials.

- The second major challenge is protecting the cells from the immune attack. To date, the only way to achieve this is by taking immune-suppressing medication, which reduces the body’s overall disease-fighting capability. Other means of cell protection, such as encapsulation, have not yet proven effective in human trials.

Demonstrated success but on a small scale

Due to the shortage of donor islets and its experimental designation, islet transplantation is only open to a limited number of people. Candidates typically have “brittle” type 1 diabetes with severe episodes of hypoglycemia.

Despite the challenges, a small number of people with T1D no longer require insulin many years after receiving an islet transplantation. For example, the DRI in Miami treats one transplant recipient who has been insulin independent for 10 years and two more who have been insulin independent for 9 years. These individuals received islet cells from cadavers and keep the cells alive by taking a combination of immune-suppressing drugs.

A short history of the current approach to islet transplantation

- Islet transplantation today follows guidelines known as the Edmonton Protocol.

- The Edmonton Protocol is established in 2000 after researchers at the University of Alberta use a combination of immune-suppressing drugs to achieve insulin independence in numerous transplant recipients. Results are published in theNew England Journal of Medicine.

- In 2001 the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases establishes the Clinical Islet Transplant Registry (CITR) to further the results achieved by the University of Alberta.

- Between 1999 and 2009, 571 people undergo islet transplantation. Throughout this time, cell supply is from cadavers and cell protection is achieved by immune-suppressing drugs. Results are discussed below.

- Many of the CITR members have not been active over the years. The 13 most active transplant centers create the Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium in 2004 (Appendix A). The first published results from the consortium are expected in the next 18 months.

Overall results from 1999-2009

Results for the 571 patients who underwent islet transplantation from 1999 to 2009 were published in the CITR’s 2010 Annual Report. As the number of years after transplantation increased, the percentage of people who remained insulin independent declined, eventually stabilizing after year 5 at 15% (Appendix B). Success levels appear to improve in the second half on the testing period. Between 1999 and 2004, 42% were insulin independent after 3 years; that number rises to 60% from 2005 to 2009 (Appendix C).

Many transplant recipients report side effects from immune suppression. Side effects include: mouth sores, indigestion, reduced kidney function, and higher susceptibility to skin cancer. For individuals who have been insulin independent for a sustained period, these side effects are described as a minor part of daily life. There was a 3% incidence of death during the study, but a direct link to transplantation remains unclear.

Next Steps

The most promising aspect of islet transplantation is the solid history of human data, some of which has been quite successful. Moving forward, we hope that two areas of research receive a meaningful increase in funding and attention:

- Finding a sustainable source of insulin-producing cells would eliminate the reliance on cadavers and be a great step forward for islet transplantation.

- Further, if the side effects related to immune suppression were reduced, the risks of immune suppression may become less than the risks associated with type 1 diabetes.

If these areas were addressed, we believe that islet transplantation could result in a Practical Cure.